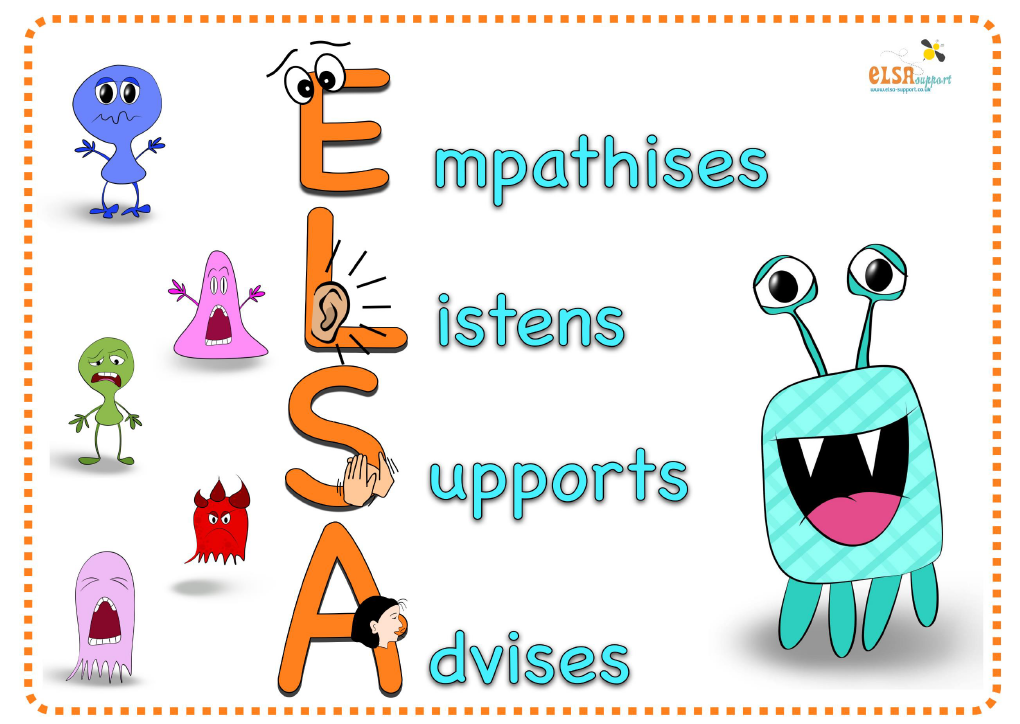

ELSAs are teaching assistants that have received additional

training from educational psychologists in order to support children and young

people in school to understand and regulate their emotions whilst also respecting

the feelings of other people around them (ELSA Network, 2017). In order for a

person to become an ELSA they must undertake six days of training on a range of

topics such as emotional awareness, self-esteem, anger management, friendships,

social communication difficulties and loss and bereavement and many more (ELSA

Network, 2013) in order to provide the ELSAs with psychological theory an

advice to give to the pupils they are helping (Burton et al., 2009).

ELSAs are teaching assistants that have received additional

training from educational psychologists in order to support children and young

people in school to understand and regulate their emotions whilst also respecting

the feelings of other people around them (ELSA Network, 2017). In order for a

person to become an ELSA they must undertake six days of training on a range of

topics such as emotional awareness, self-esteem, anger management, friendships,

social communication difficulties and loss and bereavement and many more (ELSA

Network, 2013) in order to provide the ELSAs with psychological theory an

advice to give to the pupils they are helping (Burton et al., 2009).

As stated in the name of an Emotional Literacy Support Assistant,

they link in with Emotional Literacy. Emotional Literacy can be defined as “the

ability to recognise, understand, handle and appropriately express emotions”

(Sharp, 2000, p.8). It also links in with Emotional Intelligence which is

described as consisting of five areas which are self-awareness,

self-regulation, motivation, empathy and social skills (Salovey & Mayer,

1990; Goleman, 1995). They are both used within literature as they do relate to

each other but are also different at the same time, Emotional Literacy is

mostly used in educational contexts in the UK (Qualter, Gardner & Whiteley,

2007). When the SEAL (Social and Emotional Aspects of Learning) concept was put

into the curriculum there has been a growing interest in Emotional Literacy in

schools which was made to look into and develop the social, emotional and

behavioural skills of children in education (DfES, 2005, 2007). Burton et al.

(2009) has stated that a majority of pupils that have been in the ELSA

programme or have had help from an ELSA had a positive impact when working

towards specific goals. Bravery and Harris (2009) described that ELSAs help

children to understand and express their emotions effectively and the skills

that the children learned during the ELSA sessions were able to be transferred

into the classroom or school setting (Wilding & Claridge, 2016).

In Swanage Primary School in Dorest, they have two ELSA’s within

their school who offer a range of support for the emotional needs of the

children such as recognising their emotions, anger management, loss and

bereavement, social and friendship skills and self-esteem. (Swanage Primary

School). Children are usually referred to the ELSA by their class teacher,

senior leaders or sometimes the SENCo, this primary school say that “ELSA’s are

not there to fix children’s problems. What we can do is provide emotional

support.” (Swanage Primary School) so ELSA’s are not trying to solve or fix any

problems that the children have they are there to support them and give the

children a safe space to talk about their feelings and try to build upon those

feelings.

Grahamslaw (2010) says that people who have been trained as

an ELSA have greater levels of self-efficiency and are more likely to believe

that they can make a difference to the children’s lives that they work with and

they also feel more valued within their role within the school that they are

based. In relation to the benefits that ELSAs have to children, teachers have

stated that children’s behaviour after intervention from the ELSA and the

levels of problems and hyperactivity with the children getting the intervention

decreased (Burton, Osborne & Norgate, 2010). Hills (2016) found that the

pupils appreciated having someone to talk to about their problems and feelings

in school who listened to them without criticising them and by building up a relationship

with the ELSA the children felt more accepted within the school. Hills (2016) also

found that the pupils who had someone to talk to such as an ELSA felt happier

overall due to talking about their feelings rather than bottling them all up. The

sessions that are provided to the children should be child-centred which allows

the person to see things from the perspective from the child’s point of view

and therefore offer understanding to the child (Shotton & Burton, 2019)

“Emotional Literacy is something

we model rather than teach……..Unless children experience respectful caring relationships

from others they will not know how to develop them for themselves, or even that

these are something to aim for. We gain children’s respect by giving respect”

(Shotton & Burton, 2019, p.13)

From this, I get that

to be an ELSA you need to understand your own emotions and thoughts and how to

work through them before trying to teach someone else to do it. By having

mutual respect between the ELSA and the pupils it enables them to build up a

relationship and gain a trust to talk about their thoughts and feelings.

ELSA sessions can either happen individually or in groups.

When in groups, the sessions can either be at lunchtimes or in curriculum times

but should happen at the same time and day every week to ensure consistency, they

should happen in a space where everyone feels comfortable and where there are

no/minimal interruptions (Shotton & Burton, 2019). The group sessions

should follow this general format each week: (Shotton & Burton, 2019).

- Group aims – Why are they here? What do they want to achieve?

- Establish some ground rules, the children can set these ground rules as they are in control of the sessions as they are child-led. However, there should not be too many rules to the sessions. For example, what is said in the room stays in the room or when someone speaks everyone else listens.

- Warm up activity/ ice breaker, for example pass the keys around the circle without making a noise. This will get all the children in the group working together and bonding over an activity. The activities should be suitable to the ages of the children in the group.

- Review of the week – Share one thing that has gone well this week and one thing that has gone not so well.

- Focus activity – getting to know one another or learning how to give and receive information. Games and puppets can be useful for this.

- Task for the week – Think about how you can support one another during the week in the playground or classroom. For example, looking out for another pupil in their class at playtime as they always end up on their own.

- Ask the members to make a name for their group and take photos of the group.

- To end the sessions, have a drink and a snack such as juice and biscuits – this can help the children to have an incentive for coming as they may look forward to this part of the session. It may also help them develop their social and friendship skills as they will learn how to share and socialise together.

- Remind the children of the time and place of the next meeting.

- At the end of the appropriate length of time of meeting (e.g six weeks) the member of staff could give out certificates in order to celebrate what they have learnt or to see how far they have come due to the sessions. The sessions should end once the children no longer need support or if meeting in the groups is not working for some reason.

When I was on placement a few years ago for college I was in

the outside cabin area and saw a display board for ELSA. It caught my attention

straight away and I was able to see what some of the work that the pupils and

ELSA do together. Since then I have been doing my research. In university I have

linked as much work as I can to emotional literacy or emotional intelligence in

order to find more research out about it. In my opinion I think that all primary

schools should have an area, or a room dedicated to emotional literacy. It is

so important to combat negative mental health, poor behaviour and can also help

children deal with loss and bereavement and build up their self esteem and confidence.

I think it should also be more publicised within groups and other educational

settings to build up awareness for future teachers or other people looking to work

in schools.

References:

Bravery, K., & Harris, L. (2009) Emotional literacy support assistants in Bournemouth: Impact and

outcomes. Bournemouth. Bournemouth Borough Council.

Burton, S., Osborne, C. and Norgate, R. (2010) An evaluation of the impact of the Emotional

Literacy Support Assistant project on pupils attending schools in Bridgend,

Hampshire. Educational Psychology Service Research and Evaluation Unit.

Burton, S., Traill, M., & Norgate, R. (2009) An evaluation of the emotional literacy

support assistant (ELSA) programme. Winchester: Hampshire Educational

Psychology Service, Research & Evaluation Service.

Department for Education and Skills (DfES) (2005) Excellence and enjoyment: Social and

emotional aspects of learning. London: DfES.

Department for Education and Skills (DfES). (2007) Social and emotional aspects of learning for

secondary schools. London: DfES.

ELSA Network (2017) ELSA

Network. Available at: https://www.elsanetwork.org/about/the-network/

(Accessed 28 March 2019)

ELSA Network. (2013) ELSA

Network. Available at: http://www.elsanetwork.org (Accessed

01 April 2019)

Goleman, D. (1995) Emotional

intelligence. New York, NY: Bantam Books.

Grahamslaw, L. (2010) What

is the impact of an ELSA Projecton support assistants’ and children’s self-efficiency

beliefs? Unpublished doctoral research on www.elsanetwork.org/research

Cited in: Shotton, G., Burton, S., & Agar, A. (2019). Emotional wellbeing:

An introductory handbook for schools (Second ed.).

Hills, R. (2016) An evaluation of the emotional literacy

support assistant (ELSA) project from the perspective of primary school

children. Educational and Child

Psychology, 33, 4.

Qualter, P., Gardner, K. J., & Whiteley, H. E. (2007) Emotional intelligence: Review of research

and educational implications. Pastoral Care, 25, 11–20

Salovey, P., & Mayer, J. D. (1990) Emotional

intelligence. Imagination, Cognition and Personality, 9, 185–211.

Sharp, P. (2000) Promoting emotional literacy: Emotional

literacy improves and increases your life chances. Pastoral Care in Education: International Journal of Personal, Social

and Emotional Development, 18, 8–10

Shotton, G., Burton, S., & Agar, A. (2019). Emotional wellbeing: An introductory

handbook for schools (Second ed.).

Swanage Primary School. (Unknown) ELSA – Emotional Literacy

Support. Available at: http://www.swanageprimary.dorset.sch.uk/elsa-emotional-literacy-support/

(Accessed 01 April 2019)

Wilding, Lucy, & Claridge, Simon. (2016) The Emotional

Literacy Support Assistant (ELSA) Programme: Parental Perceptions of Its Impact in School and at Home. Educational

Psychology in Practice, 32(2), 180-196.